There's an interesting study out of Australia that analyzed the affects of reading on iPads on student reading comprehension. I was particularly interested in this study for two reasons: first, because this is after all a blog about tablets, and second, because the study was conducted with sixth-graders and I once was a sixth-grade reading teacher. Therefore, I definitely could empathize with the teachers and students in the study who were struggling to implement the use of iPads in the classroom.

The basic set-up of the study was comprised of two sets of students--one control group reading traditional textbooks, and another experimental group reading epubs on iPads. The experiment was conducted soon after the release of the first iPad, so one should take that fact into consideration of the validity of the study, as Apple has improved upon the original iPad and the overall textbook epub reading experience since then. The control group and experimental group were subdivided by students' reading ability, so that each group had a Low, Middle, and High group as well. The students read The Adventures of Tom Sawyer by Mark Twain among other readings.

The study ultimately found that further study would be required to make a definitive statement about whether iPads significantly impact student reading. However, the study found that the experimental group (the ipad group) performed worse than the control group (the textbook group) on standardized reading comprehension group. In particular, the Low experimental group performed the poorest of all. The researches proposed that the iPads, while exciting and shiny-new, presented a distraction to students which negatively affected students' reading comprehension.

I would like to see the same experiment conducted using the latest iPads today to see if there is a difference in the result, given the improvements that Apple has made in the two years since the study came out. I think that there might be a slight improvement in the experimental group's test scores because iPads aren't the novel gadgets that they once were. In other words, teachers and students alike have more experience using iPads nowadays, so the teachers and students might not be as distracted and/or intimidated by the technology as they once were. I wouldn't be surprised however--as someone who often gets distracted while reading a book on my tablet--if the textbook group outperformed the iPad group a second time around.

References

Sheppard, D. (2011). Reading with iPads—the difference makes a difference. Education Today, 13(1), 12-15. Retrieved from:http://www.minnisjournals.com.au/articles/ipads%20et%20t3%2011.pdf

Monday, April 29, 2013

Starting up a library iPad program: Success and Failure

When I started this blog, I mentioned some of my personal frustration with getting a library iPad program off the ground. So, in search of some advice I stumbled across this excellent article from the Association of Colleges & Research Libraries on setting up just such a program at Briar Cliff University with some helpful guidelines for success. It would have been nice if I'd read this case study before I proposed my own program last year. More on that in a moment.

If you are considering creating a library iPad program I would highly recommend you read the article in full, but here are some highlights/tips:

- Apple has introduced an App Volume Purchase Program to facilitate app purchasing for institutions. Use this program to set up your apps across multiple devices and to maintain your backups.

- Restrict the iTunes settings of the iPads so that borrows cannot purchase apps, since these apps will just be wiped upon return.

- When the iPads are returned use the "Erase all content and settings" feature to wipe data clean.

- BCU instituted a $15 an hour late fee and $700 loss replacement fee with a loan period of 4 hours at first, which was later switched to 2 days for undergraduates.

- "Provide patrons with an easy way to suggest apps and set a maximum price that the library will pay for an app or a maximum total for all apps" (Thompson, 2011).

The article also included some great some detailed logistical advice and a robust list of app recommendations. While this information certainly would have aided me in my attempt to create a library iPad program, it would not have helped me to overcome the biggest obstacle that I faced: liability concerns.

In short, and without getting into the particular details, the reason my library iPad program never got off the ground was because I eventually found out that students would not be able to take the iPads off-campus due to university policy regarding equipment liability. And after conducting a series of formal and informal surveys, there simply was not enough demand for a iPad loan program that did not allow students to take the iPads out of the building with them. It's an unfortunate situation, but I have still managed to get some use out of our iPads by using them to conduct other library surveys about library services and student needs.

References

Thompson, S. (2011). Setting up a library iPad program: guidelines for success. C&RL News, 72(4). Retrieved from http://crln.acrl.org/content/72/4/212.full

Tablets for the uninitiated--A PowerPoint Tutorial

Introduction

- Did you just buy a tablet and want to learn how to use it?

- Are you thinking about buying a tablet, but haven’t made the leap yet?

- Did your kids buy a tablet for you and you haven’t taken it out of the box yet?

- This guide will walk you through the basics of tablet computing and familiarize you with some of the best ways to enjoy your tablet.

Overview

- Designed with all tablets in mind

- Android and iOS friendly

- Advantages of using a tablet

- The home screen

- Connecting to the Internet

- Apps and app stores

- Web browsing

- Using e-mail

- Reading and downloading e-books

- Streaming video

The advantages of using a tablet

- Portability—easy to use on the go, or lounging on the couch. Not as cumbersome as a laptop and typically has a longer battery life.

- Ease of use—once you learn the basics, tablets are very user- friendly

- Great for book lovers—Instead of lugging around a stack of books for a long weekend at the beach, bring your tablet and enjoy having thousands of books at your fingertips.

- Great for browsing the internet and reading the news.

- Can be good for people with poor eyesight because you are able to enlarge text to meet your reading needs.

Android or OS?

- There are two major operating systems for tablets today: Android, developed by Google, and iOS, developed by Apple.

- If you have an Ipad or Ipad mini you will be using the iOS platform.

- If you have any other tablet—e.g. Kindle, Nook, Nexus, or Galaxy, to name a few popular brands– then you will be using the Android platform.

- We will go over the basics of both operating systems together, so don’t worry if you don’t know which specific version of Android or iOS you have.

The home screen

- When you turn-on or wake your tablet you will see the home screen.

- Tapping on an icon, the small square or circle shaped objects on the screen, will open various apps for use.

- You can organize your home screen by long-pressing on an icon (holding your finger down for more than one second) and dragging the icon to your desired location.

Connecting to the Internet (Wi-Fi)

Apps

- Apps, short for applications, are represented by small colorful icons

- Unlike the programs that you double-click on to open on your home computer, you can access apps with the tap of your finger on your tablet.

- You can group related apps together by long-pressing on apps and dragging an icon on top of another icon.

App Stores

- Several apps come preinstalled on your tablet, but you will want to install more apps from the app store.

- Don’t let the word ‘store’ intimidate you. Many of the best apps are absolutely free, however, you will need to set up your account with a credit card the first time using the app store.

- Some users purchase many apps, others none whatsoever, so it’s really up to your preference.

- If you are not using an iPad the app store might go by a slightly different name so look for an icon called “Amazon Apps” or “Google Play” or “Samsung Apps” depending on your tablet. Tap on the icon to open the app store.

Reading and Composing Emails

- When you first turned on your tablet you were probably prompted to link your email address to your device. (If not, go to Settings>Mail>Add Account>select your email provider and enter your email address).

- To check your email find the “Mail” or “Gmail” app and open it.

- From there you can read your emails and compose and send emails using your on-screen keyboard.

- Some users like the feel of a tactile keyboard so if you enjoy writing emails on your tablet, then you might want to invest in a Bluetooth keyboard to write longer emails.

Reading ebooks and ebook purchasing

- There are many different ways to read e-books on your tablet.

- The most commonly used e-book reader apps are Kindle, iBooks (Apple only), Nook, and Google’s ‘Play Books’ app (see icons left to right above). You will need to install these apps first in order to use them.

- Once you’ve installed the app, you can purchase books from the store--look for the store button within the app--and download them to read.

- There are thousands of older books that are free to download because they are in the public domain and no longer under copyright protection. Now is the perfect time to download a copy of War and Peace or Moby Dick and you won’t have thumb through a heavy book to read them! Change the font, resize the text, the options are many.

- Another feature for book lovers is that you can download a book sample, usually the first 2 chapters of a book, and begin reading the book. If you like it, you can buy it to continue reading.

Streaming video services

- To watch videos on your device you can install apps such as YouTube, Netflix, and Hulu.

- These apps are free to install but Netflix and Hulu+ require an account use.

- Movies can be rented or purchased as well via the iTunes store or various App stores.

Conclusion

- I hope that you feel a bit more comfortable now with using a tablet and doing some basic tasks.

- I hope you learned something new and that these basic skills will enhance your tablet using experience.

- If you’ve just purchased a new iPad, you may be eligible for a free 1 hour workshop at your local Apple genius bar as well: https://www.apple.com/retail/learn/

- For further information please don’t hesitate to ask your friendly librarian to assist you in locating resource materials and finding other help sessions.

Are ebooks and tablets changing the way we read?

I read an interesting Guardian article recently entitled "Why ebooks are a different genre from print" that got me thinking about the question of whether ebooks and tablets are changing the way we read. And if they are, is that a good thing? The article identified two key ways that ebooks change the reader's relationship with the text:

With the book, the reader's relationship to the text is private, and the book is continuous over space, time and reader. Neither of these propositions is necessarily the case with the ebook.Contra to the good old fashioned codex, the reader's relationship to the text is increasingly less private as more and more information about our reading habits is collected and tracked by various interested parties: makers of e-book apps, tablets, and publishing companies. So for example, if a publisher or author learns that a third of readers who purchased a book failed to finish chapter three, then they could make future decisions reflecting that knowledge. Unfortunately, there isn't much data available about what publishers are doing with this data just yet. But this is truly uncharted territory and it will be interesting to see what readers and publishers do with this new information. I worry that one day soon an author, informed with information that a large percentage of readers did not finish a difficult chapter, might change the way they write to accommodate shorter attention spans. But then again, this new information might help authors and publishers produce better quality books. It's difficult to say at this point.

Another thing to think about is how our relationship to the text is changing when we read a book in ebook format. Consider how, when reading a Kindle book, you can turn on a feature that allows you to view the most highlighted passages by other users. When I first used this feature I was amazed that I could find out whether other people highlighted the same passages that I did; it also had the negative affect of making me a bit self-conscious when I learned that passages I loved were not loved by other readers. Upon some future reflection, I also wondered if this "crowdsourced" feature could create a sort of group-think opinion about a book, where people might assign an undue amount of significance to a passage simply because other people highlighted it.

So to return to the initial question, I think there is some budding evidence, albeit largely untested and anecdotal at this point, that ebooks and tablets are changing the way we read. We know that the solitary act of reading is no longer quite as solitary as it once was now that companies can track the reading habits of ebook readers. And we know that we can find instant opinion about the most highlighted passages in any given book on our Kindles or using the Kindle app. I think it would be unwise, however, at this early stage to say that they are changing things for the better or worse.

From Papyrus to Total Noise: A Chronology of LIS Technology

Maybe you've seen the "Medieval Helpdesk" sketch from Norway about a monk struggling to use a book. Check it out first if you haven't:

Funny as it as, historians of librarianship know that the monk in the comedy sketch would have been using books for a millienium, as the codex was introduced in the 1st century CE. Here's a more accurate chronology of LIS Technology for your reading pleasure.

How did we get here?

What follows is an exploration of the

history of technology in the field of Library and Information Science. The

primary question guiding this research was “how did we get from point A to

point B?”, with point B representing our technologically rich present in which

most Americans have access to, in the words of David Foster Wallace, “a tsunami

of available fact, context, and perspective that constitutes Total Noise”—our

abundance of information (2007).As with any chronology, each milestone

chosen was a deliberate decision—an interpretative act, as it were—about the

most important events in shaping LIS technology. Therefore, since no chronology

can be truly comprehensive, my task is to persuasively demonstrate why each

chosen event bears careful consideration.

How do we define Technology?

- Thanks to the dawn of computing and the digital age, today we often conceive of technology in terms of electronic or digital products in the marketplace.

- However, There is older definition, used particularly among anthropologists, that might better suit our purposes.

- This broader definition of technology is: “The body of knowledge available to a society that is of use in fashioning implements, practicing manual arts and skills, and extracting or collecting materials” (2002).

Where to begin?

- With this broader definition of technology in mind, one must consider, what is referred to in the field of History as the problem of periodization. In other words, when does the history of LIS Technology begin in earnest?

- Even if we are narrowly interested in the development of today’s LIS computers, I argue that we must begin with one of the earliest forms of information storage media: the papyrus scroll.

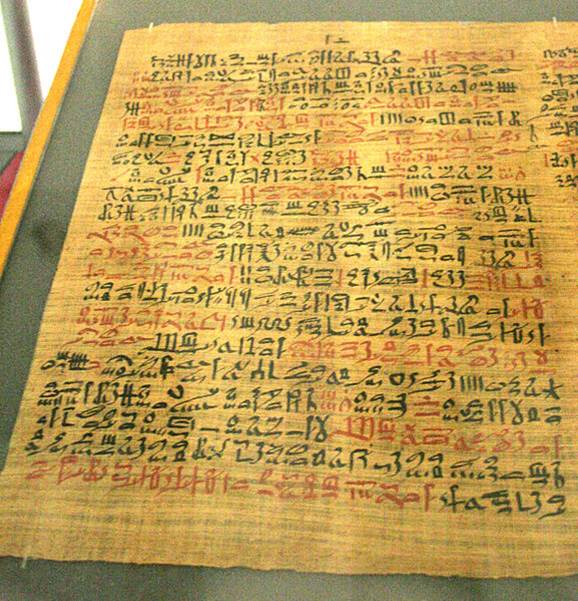

Papyrus Scroll (3rd millenium BCE)

- The papyrus scroll was invented by the Egyptians as a way to record, retrieve, and preserve written documents (Burke, 2009).

- Scrolls were a notable improvement over the stone and clay tablets used by the ancient Sumerians and the Indus River Valley civilization (Purdy, Prono, & Parcak, 2006).

Codex (1st c. CE)

- Paper writings were bound into books—a more portable and easier to read technology than scrolls (Burke, 2009).

- The book making process however was still tediously lengthy, as books had to be produced by scribes, usually monks, and written by hand (n.d., 2012).

Printing Press (15th c. CE)

- The Gutenberg printing press revolutionized the making of books by drastically reducing the costs of production and distribution (n.d., 2011).

- With the reduction in cost, the audience for books was greatly expanded and thus the printing press was pivotal in the dissemination of the written word and the spread of ideas (Burke, 2009).

Universal Classification Systems (1876)

- With the advent of the printing press, the need for libraries to organize books became apparent (n.d., 2012).

- Initially, libraries adopted their own systems of organization, but later, beginning in 1876, Melvil Dewey devised his Decimal System to arrange books according to subject. Today, the DDC and the LCC are the most common systems of classification used in the US (Burke, 2009).

Automated Library Systems & MARC (early 1960s)

- Methods of displaying bibliographic records have evolved significantly from early manuscript catalogs, to card catalogs , to todays OPACs, however, a key development along the way was the creation of automated library systems such as MARC (Machine-Readable Cataloging) which is an intricate encoding system that is used to this day (Burke, 2009).

- Since 1999, MARC 21 has provided a universal encoding schema for the representation and communication of descriptive metadata (Chan & Hodges, 2007).

Moore’s

Law

- Once we reach the dawn of the computer age, one should consider Moore’s Law, Gordon E. Moore was a cofounder of Intel, which states that the number of transistors in an integrated circuit would double every two years.

- His theory has proved remarkably prescient regarding the exponential growth of computing power since the early 1970s as seen in the chart on the right.

The Personal Computer (circa mid 80s—today)

- Perhaps the most used instrument of technology in libraries today is the PC. While PCs were introduced in the 1960s they were somewhat cumbersome for ordinary use until user-friendly operating systems, such as Windows and Mac OS, were introduced in the early 90s (Burke, 2009).

- Thanks to Moore’s Law, the system specs, or hardware, of PCs continues to rapidly evolve, even if (as we see on the right) the overall design of PCs has not changed too much in the last 20 years (Reichardt, R., & Cox, C. 2006)

The Internet (mid 90s)

- While the Internet was first conceived in the 1960s and arguably even as early as WWII, it was not ubiquitous in libraries until the 1990s (Burke, 2009).

- The availability of the Internet and online searching has provided library patrons and librarians with a wealth of information and has dramatically shifted how we seek for and retrieve information today; although, an abundance of information presents librarians with distinct advantages and disadvantages (see Rubin, 2010).

The mobile library (late

2000s): handhelds, phones, tablets, ebook readers

- Increasingly, library patrons and librarians are using handheld devices to browse OPACs, check-out download and read e-books, and even conduct research on the go (Rubin, 2010).

- Libraries such as my own (UGA Libraries) are placing significant importance on the mobile experience to accommodate the information needs of library patrons.

Cloud Computing (late 2000s)

- Cloud computing is an important development for LIS technology because it could conceivably eliminate the need for libraries to house physical containers of information (e.g., books, CDs, DVDs, microfilm, etc.) and replace such containers with data center networks that allow users access to information via the Internet.

- It is unlikely that physical containers will not disappear in our lifetimes, however, cloud computing could potentially revolutionize the modern library as we know it. (Rubin, 2010).

Conclusion

- We began our chronology with the earliest of media storage devices, papyrus, so it is fitting to close with the latest of media storage devices—the cloud. The future of LIS technology is sure to bring surprises as well as improvements of PCs and the interconnectivity of technological devices.

- As this chronology demonstrates, library technology was and continues to be driven by innovation in information storage, access, production, and retrieval. Libraries appear to be in period of flux, with Internet access and online searching changing the very ways we think about information retrieval. But amid such “Total Noise,” the library continues to play a critical institutional role in the organization of information and the leader in adopting and advancing technological innovation.

Work

Cited

Burke, J. (2009). Neal-Schuman

library technology companion: A basic guide for library staff (3rd

ed.). New York: Neal-Schuman Publishers.

Chan, L. M., & Hodges, T.

(2007). Cataloging and classification: An introduction (3rd

ed.). Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press.

Dewey Decimal Classification. (2012). In Encylopedia

Britannica.

Retrieved from www.britannica.com

Houghton Mifflin Company. (2002). The

American Heritage college dictionary (4th ed.).

Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Printing Press. (2011). In Encylopedia

Britannica.

Retrieved from www.britannica.com

Purdy, E., Prono, L., & Parcak, S.

(2006). Egypt, ancient. In H. Birx (Ed.), Encyclopedia

of anthropology.(pp.

788-798). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE

Publications, Inc. doi:

10.4135/9781412952453.n274

Reichardt, R., & Cox, C. N. (2006). Moore's

Law and the Pace of Change. Internet Reference Services Quarterly, 11(3), 117-124.

Rubin, R. (2010). Foundations

of library and information science, New York : Neal- Schuman Publishers, 3rd

edition.

Wallace, David Foster (2007). The

Best American essays.

New York: Ticknor & Fields.

Picture Credits

All images available via Wikimedia

Commons and in accordance with Creative Commons licensing. http://commons.wikimedia.org/

Thursday, April 25, 2013

Netflix for Books?

I recently read an intriguing article from Wired about the unveiling of a subscription service for short story e-books. The service was announced by the UK bookstore, Waterstones, and according to the article, there's another such streaming e-book service currently operating called F+W Media, which caters to romance genre enthusiasts. I'd never heard of a subscription service for books before, but one can imagine the possibilities if subscription e-book services were to take off.

The first thing that struck me was that these subscription models are currently catering toward specific genre audiences, which seems like a shrewd decision. As the Wired piece notes, while it might be easy to watch a few dozen episodes of a TV show on Netflix in a month, it's not as easy to read several books in a month. Therefore, the subscription model makes more sense for people who are heavy-readers and can read through books quickly--which is exactly the case for romance novel readers and short story lovers. There are other genres that might fit the delivery model criteria: thrillers, mysteries, true-crime, and maybe fantasy and sci-fi (although some of these books are very large). I'm sure there are other groups of readers too that might benefit from a subscription service.

But I'm not quite as optimistic as Wired that e-book subscriptions will flourish in the long-term because of the fleeting nature of the delivery model and the lack of broad-based appeal that subscription models have beyond niche markets. For example, what if I like owning my books and being able to look back on them? Will I be able to review the passages I highlighted or notes I made in the margins with a subscription plan? And what about readers who like literary fiction or non-fiction books; how would this service be made appealing to them?

Also worth considering are the tricky logistics of setting up subscriber networks. A critical question for me is how many people will be able to "check out" a title at once? If only so many people can read a title at once (and I suspect that will be the case given our current intellectual property laws and licensing agreements), are private companies just creating their own parallel digital queues for popular e-books, as currently exists for popular public library e-books?

As titilating of an idea as a Netflix for books might sound to bibliophiles, for the reasons I've cited above, I think we're still years away before we'll have a multi-genre, multi-publisher, wide-reaching e-book subscription service available to use on our e-readers and tablets. But there are reasons for optimism for the success of the subscription based model. The Kindle Lending Library, which makes 300,000 books available to Amazon Prime users who own Kindles, is certainly a service that deserves attention. I have Amazon Prime, but I don't own a Kindle, so I'm curious to hear what users of the Kindle Lending Library think. I could be way off the mark here. As with all technological speculation, only time will tell.

The first thing that struck me was that these subscription models are currently catering toward specific genre audiences, which seems like a shrewd decision. As the Wired piece notes, while it might be easy to watch a few dozen episodes of a TV show on Netflix in a month, it's not as easy to read several books in a month. Therefore, the subscription model makes more sense for people who are heavy-readers and can read through books quickly--which is exactly the case for romance novel readers and short story lovers. There are other genres that might fit the delivery model criteria: thrillers, mysteries, true-crime, and maybe fantasy and sci-fi (although some of these books are very large). I'm sure there are other groups of readers too that might benefit from a subscription service.

But I'm not quite as optimistic as Wired that e-book subscriptions will flourish in the long-term because of the fleeting nature of the delivery model and the lack of broad-based appeal that subscription models have beyond niche markets. For example, what if I like owning my books and being able to look back on them? Will I be able to review the passages I highlighted or notes I made in the margins with a subscription plan? And what about readers who like literary fiction or non-fiction books; how would this service be made appealing to them?

Also worth considering are the tricky logistics of setting up subscriber networks. A critical question for me is how many people will be able to "check out" a title at once? If only so many people can read a title at once (and I suspect that will be the case given our current intellectual property laws and licensing agreements), are private companies just creating their own parallel digital queues for popular e-books, as currently exists for popular public library e-books?

As titilating of an idea as a Netflix for books might sound to bibliophiles, for the reasons I've cited above, I think we're still years away before we'll have a multi-genre, multi-publisher, wide-reaching e-book subscription service available to use on our e-readers and tablets. But there are reasons for optimism for the success of the subscription based model. The Kindle Lending Library, which makes 300,000 books available to Amazon Prime users who own Kindles, is certainly a service that deserves attention. I have Amazon Prime, but I don't own a Kindle, so I'm curious to hear what users of the Kindle Lending Library think. I could be way off the mark here. As with all technological speculation, only time will tell.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)