Maybe you've seen the "Medieval Helpdesk" sketch from Norway about a monk struggling to use a book. Check it out first if you haven't:

Funny as it as, historians of librarianship know that the monk in the comedy sketch would have been using books for a millienium, as the codex was introduced in the 1st century CE. Here's a more accurate chronology of LIS Technology for your reading pleasure.

How did we get here?

What follows is an exploration of the

history of technology in the field of Library and Information Science. The

primary question guiding this research was “how did we get from point A to

point B?”, with point B representing our technologically rich present in which

most Americans have access to, in the words of David Foster Wallace, “a tsunami

of available fact, context, and perspective that constitutes Total Noise”—our

abundance of information (2007).As with any chronology, each milestone

chosen was a deliberate decision—an interpretative act, as it were—about the

most important events in shaping LIS technology. Therefore, since no chronology

can be truly comprehensive, my task is to persuasively demonstrate why each

chosen event bears careful consideration.

How do we define Technology?

- Thanks to the dawn of computing and the digital age, today we often conceive of technology in terms of electronic or digital products in the marketplace.

- However, There is older definition, used particularly among anthropologists, that might better suit our purposes.

- This broader definition of technology is: “The body of knowledge available to a society that is of use in fashioning implements, practicing manual arts and skills, and extracting or collecting materials” (2002).

Where to begin?

- With this broader definition of technology in mind, one must consider, what is referred to in the field of History as the problem of periodization. In other words, when does the history of LIS Technology begin in earnest?

- Even if we are narrowly interested in the development of today’s LIS computers, I argue that we must begin with one of the earliest forms of information storage media: the papyrus scroll.

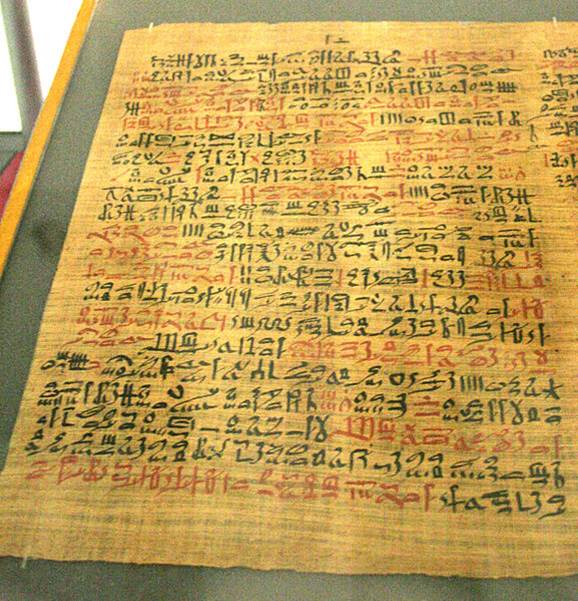

Papyrus Scroll (3rd millenium BCE)

- The papyrus scroll was invented by the Egyptians as a way to record, retrieve, and preserve written documents (Burke, 2009).

- Scrolls were a notable improvement over the stone and clay tablets used by the ancient Sumerians and the Indus River Valley civilization (Purdy, Prono, & Parcak, 2006).

Codex (1st c. CE)

- Paper writings were bound into books—a more portable and easier to read technology than scrolls (Burke, 2009).

- The book making process however was still tediously lengthy, as books had to be produced by scribes, usually monks, and written by hand (n.d., 2012).

Printing Press (15th c. CE)

- The Gutenberg printing press revolutionized the making of books by drastically reducing the costs of production and distribution (n.d., 2011).

- With the reduction in cost, the audience for books was greatly expanded and thus the printing press was pivotal in the dissemination of the written word and the spread of ideas (Burke, 2009).

Universal Classification Systems (1876)

- With the advent of the printing press, the need for libraries to organize books became apparent (n.d., 2012).

- Initially, libraries adopted their own systems of organization, but later, beginning in 1876, Melvil Dewey devised his Decimal System to arrange books according to subject. Today, the DDC and the LCC are the most common systems of classification used in the US (Burke, 2009).

Automated Library Systems & MARC (early 1960s)

- Methods of displaying bibliographic records have evolved significantly from early manuscript catalogs, to card catalogs , to todays OPACs, however, a key development along the way was the creation of automated library systems such as MARC (Machine-Readable Cataloging) which is an intricate encoding system that is used to this day (Burke, 2009).

- Since 1999, MARC 21 has provided a universal encoding schema for the representation and communication of descriptive metadata (Chan & Hodges, 2007).

Moore’s

Law

- Once we reach the dawn of the computer age, one should consider Moore’s Law, Gordon E. Moore was a cofounder of Intel, which states that the number of transistors in an integrated circuit would double every two years.

- His theory has proved remarkably prescient regarding the exponential growth of computing power since the early 1970s as seen in the chart on the right.

The Personal Computer (circa mid 80s—today)

- Perhaps the most used instrument of technology in libraries today is the PC. While PCs were introduced in the 1960s they were somewhat cumbersome for ordinary use until user-friendly operating systems, such as Windows and Mac OS, were introduced in the early 90s (Burke, 2009).

- Thanks to Moore’s Law, the system specs, or hardware, of PCs continues to rapidly evolve, even if (as we see on the right) the overall design of PCs has not changed too much in the last 20 years (Reichardt, R., & Cox, C. 2006)

The Internet (mid 90s)

- While the Internet was first conceived in the 1960s and arguably even as early as WWII, it was not ubiquitous in libraries until the 1990s (Burke, 2009).

- The availability of the Internet and online searching has provided library patrons and librarians with a wealth of information and has dramatically shifted how we seek for and retrieve information today; although, an abundance of information presents librarians with distinct advantages and disadvantages (see Rubin, 2010).

The mobile library (late

2000s): handhelds, phones, tablets, ebook readers

- Increasingly, library patrons and librarians are using handheld devices to browse OPACs, check-out download and read e-books, and even conduct research on the go (Rubin, 2010).

- Libraries such as my own (UGA Libraries) are placing significant importance on the mobile experience to accommodate the information needs of library patrons.

Cloud Computing (late 2000s)

- Cloud computing is an important development for LIS technology because it could conceivably eliminate the need for libraries to house physical containers of information (e.g., books, CDs, DVDs, microfilm, etc.) and replace such containers with data center networks that allow users access to information via the Internet.

- It is unlikely that physical containers will not disappear in our lifetimes, however, cloud computing could potentially revolutionize the modern library as we know it. (Rubin, 2010).

Conclusion

- We began our chronology with the earliest of media storage devices, papyrus, so it is fitting to close with the latest of media storage devices—the cloud. The future of LIS technology is sure to bring surprises as well as improvements of PCs and the interconnectivity of technological devices.

- As this chronology demonstrates, library technology was and continues to be driven by innovation in information storage, access, production, and retrieval. Libraries appear to be in period of flux, with Internet access and online searching changing the very ways we think about information retrieval. But amid such “Total Noise,” the library continues to play a critical institutional role in the organization of information and the leader in adopting and advancing technological innovation.

Work

Cited

Burke, J. (2009). Neal-Schuman

library technology companion: A basic guide for library staff (3rd

ed.). New York: Neal-Schuman Publishers.

Chan, L. M., & Hodges, T.

(2007). Cataloging and classification: An introduction (3rd

ed.). Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press.

Dewey Decimal Classification. (2012). In Encylopedia

Britannica.

Retrieved from www.britannica.com

Houghton Mifflin Company. (2002). The

American Heritage college dictionary (4th ed.).

Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Printing Press. (2011). In Encylopedia

Britannica.

Retrieved from www.britannica.com

Purdy, E., Prono, L., & Parcak, S.

(2006). Egypt, ancient. In H. Birx (Ed.), Encyclopedia

of anthropology.(pp.

788-798). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE

Publications, Inc. doi:

10.4135/9781412952453.n274

Reichardt, R., & Cox, C. N. (2006). Moore's

Law and the Pace of Change. Internet Reference Services Quarterly, 11(3), 117-124.

Rubin, R. (2010). Foundations

of library and information science, New York : Neal- Schuman Publishers, 3rd

edition.

Wallace, David Foster (2007). The

Best American essays.

New York: Ticknor & Fields.

Picture Credits

All images available via Wikimedia

Commons and in accordance with Creative Commons licensing. http://commons.wikimedia.org/

No comments:

Post a Comment